Uncle Jim

Uncle Jim was a tall lanky Scotsman, a quiet unassuming chap. He had married my Mothers younger sister in 1946, aged just 26, and their only Daughter Sally was much the same age as me. We knew he had been a Sergeant in the Scots Guards and had served with the Long Range Desert Group in North Africa. The commendation hanging in their hallway was a testament to his bravery, and the slight limp when he walked a reminder he was shot in the leg.

Rumour was that he was wounded behind enemy lines, and had to stay quiet as he was carried out past enemy positions. As was the way, he never spoke of the war, and sadly we never asked.

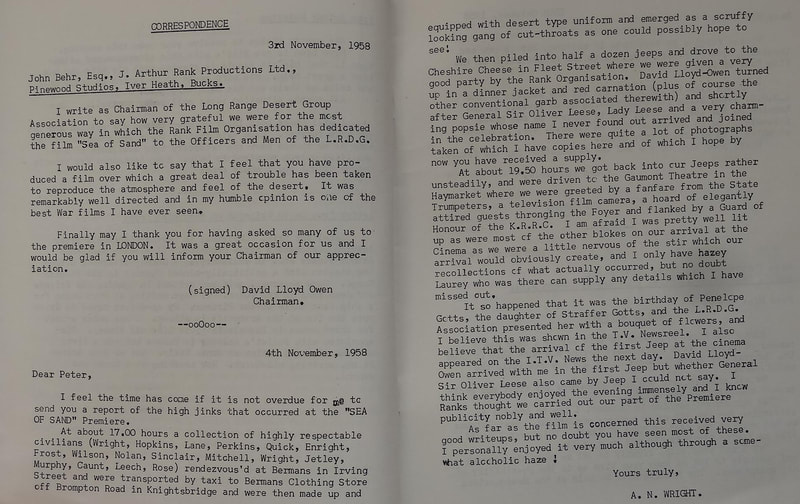

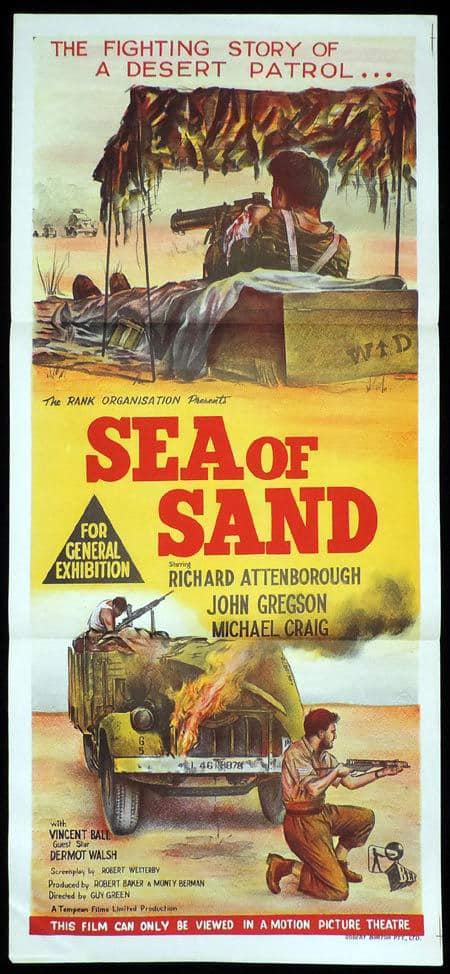

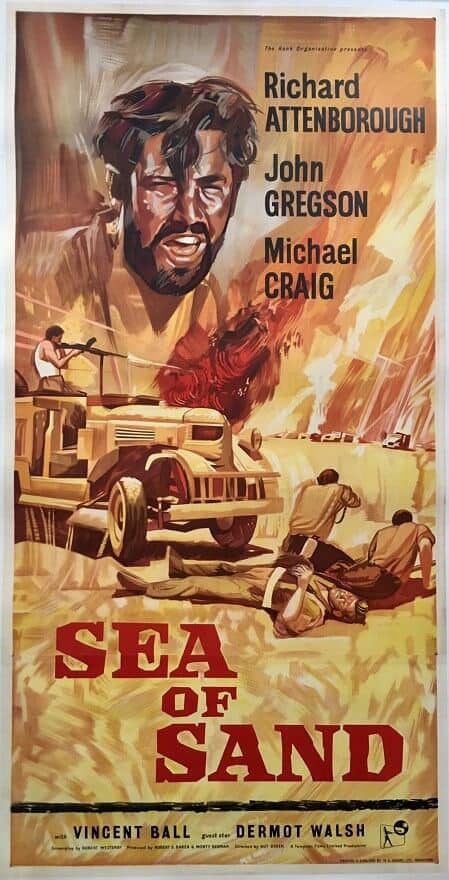

He did once mention to me he was a guest of honour at the premier of ‘Sea of Sand’ in London, a 1958 film about the exploits of the

LRDG. Apparently just 17 of the surviving members of Bagnold’s desert commandos were traced, dressed in their Arabian ‘uniform’,and ferried to the Theatre in Willy’s Jeeps. His only comment on the film was that they had good vehicles – he said in reality the LRDG had a hotchpotch of different vehicles begged, borrowed or stolen from wherever, including the Italians and Germans!

A gentle, quietly spoken person with a good sense of humour, he just got on with a very ordinary life of working during the week and fishing at weekends. His wartime exploits had earned him the respect of his peers, he had done more than his bit and we

were all quite proud, and that was enough.

He died in 2003, and the local Vicar was a frequent visitor during the last weeks before his death. He had obviously chatted at some length with Jim, and gathered much information, which he recounted during his address to those gathered at Jim’s funeral.

It was no surprise he mentioned Jim's service with the LRDG, but there was more. We had all assumed he had been invalided out of the war, but in fact he had returned to London, and ‘spent some time on bomb disposal duty’. Following this he was assigned to guarding Buckingham Palace. Then as a finale, after the war he was recruited into the newly reformed SAS.

It seems he had ‘forgot to mention’ these later exploits.

His daughter Sally was as amazed as anyone.

Oh, and along the way he was awarded the Military Medal. He had ‘forgot to mention’ that as well.

The citation reads:

14/10/1943 James Wilson 318000 Scots Guards attd. LRDG

“Since Sgt Wilson joined the LRDG over two years ago he has not missed a single operation of his Patrol, and on every

occasion has displayed conspicuous courage and devotion to duty.

When wounded in action in Jan 1941, he suffered much pain with the utmost fortitude while being carried over 1000 miles over bumpy desert in a truck before reaching a dressing station.

He was a member of a small party which carried out a successful census of enemy traffic behind the lines in the JEBEL in March 1942.

This was carried out under the most arduous conditions, involving a walk of 60 miles carrying much kit, but Sgt Wilson’s personal example made the task seem easy to the men under him.

In July 1942 he displayed particular gallantry in attending to his wounded officer, remaining with him, exposed to heavy fire from enemy fighter aircraft.

Throughout his service with the LRDG, Sgt Wilson has been an admirable example to the men in his Patrol.”

Signed:

Guy Prendergast, Lt Col. Comdg. LRDG

Bernard L Montgomery,

Gen. Eighth Army

Note that having been shot in the leg in Jan 1941, not only did he just carry on as before, but 14 months later walked 60 miles across a desert. The wound was such that he could only walk with the aid of a stick in later life.

He was credited with having been the soldier transported the furthest in WW2 having been wounded in action and taken to the nearest dressing station.

Rumour was that he was wounded behind enemy lines, and had to stay quiet as he was carried out past enemy positions. As was the way, he never spoke of the war, and sadly we never asked.

He did once mention to me he was a guest of honour at the premier of ‘Sea of Sand’ in London, a 1958 film about the exploits of the

LRDG. Apparently just 17 of the surviving members of Bagnold’s desert commandos were traced, dressed in their Arabian ‘uniform’,and ferried to the Theatre in Willy’s Jeeps. His only comment on the film was that they had good vehicles – he said in reality the LRDG had a hotchpotch of different vehicles begged, borrowed or stolen from wherever, including the Italians and Germans!

A gentle, quietly spoken person with a good sense of humour, he just got on with a very ordinary life of working during the week and fishing at weekends. His wartime exploits had earned him the respect of his peers, he had done more than his bit and we

were all quite proud, and that was enough.

He died in 2003, and the local Vicar was a frequent visitor during the last weeks before his death. He had obviously chatted at some length with Jim, and gathered much information, which he recounted during his address to those gathered at Jim’s funeral.

It was no surprise he mentioned Jim's service with the LRDG, but there was more. We had all assumed he had been invalided out of the war, but in fact he had returned to London, and ‘spent some time on bomb disposal duty’. Following this he was assigned to guarding Buckingham Palace. Then as a finale, after the war he was recruited into the newly reformed SAS.

It seems he had ‘forgot to mention’ these later exploits.

His daughter Sally was as amazed as anyone.

Oh, and along the way he was awarded the Military Medal. He had ‘forgot to mention’ that as well.

The citation reads:

14/10/1943 James Wilson 318000 Scots Guards attd. LRDG

“Since Sgt Wilson joined the LRDG over two years ago he has not missed a single operation of his Patrol, and on every

occasion has displayed conspicuous courage and devotion to duty.

When wounded in action in Jan 1941, he suffered much pain with the utmost fortitude while being carried over 1000 miles over bumpy desert in a truck before reaching a dressing station.

He was a member of a small party which carried out a successful census of enemy traffic behind the lines in the JEBEL in March 1942.

This was carried out under the most arduous conditions, involving a walk of 60 miles carrying much kit, but Sgt Wilson’s personal example made the task seem easy to the men under him.

In July 1942 he displayed particular gallantry in attending to his wounded officer, remaining with him, exposed to heavy fire from enemy fighter aircraft.

Throughout his service with the LRDG, Sgt Wilson has been an admirable example to the men in his Patrol.”

Signed:

Guy Prendergast, Lt Col. Comdg. LRDG

Bernard L Montgomery,

Gen. Eighth Army

Note that having been shot in the leg in Jan 1941, not only did he just carry on as before, but 14 months later walked 60 miles across a desert. The wound was such that he could only walk with the aid of a stick in later life.

He was credited with having been the soldier transported the furthest in WW2 having been wounded in action and taken to the nearest dressing station.

Long Range Desert Group

Their theatre of war was the Libyan Desert, the size of India, 1200 by 1000 miles, containing the impassable Sand Sea, the size of Ireland.

The desert war ran from December 1940 to March 1943 and was the place the Germans and Italians were first defeated.

Patrols were designed with a 1500-mile capability & over 25 days supplies, although it was common to double this.

Despite being a secret clandestine group, its reputation was such that there was never any shortage of volunteers, just the difficulty of finding the right ones. At one point 12 recruits were taken from 700 volunteers and on another 20 were taken from 500 interviewed.

One recruit, arriving on Christmas Day, was found unsuitable, and at 7.30am on Boxing Day found to his dismay he was on his way back to his original unit.

Their prime directive was to gather intelligence about enemy movements hundreds of miles behind the front lines without their presence being known, but they were also involved in frequent attacks on enemy airfields and garrisons, appearing from nowhere and melting away afterwards. They often appeared to be a bigger force than they were, confusing the enemy as to a major offensive, and causing them to deploy valuable resources to guarding their long supply lines.

They numbered just 90 at the start, rising to around 350, including support staff. As they went about exploring uncharted deserts, they produced the first detailed maps, and latterly found routes to outflank Rommel and literally led the eighth army units through previously impassable terrain in pincer movements around German defences.

The LRDG were the first special forces unit, later followed by the SAS. The SAS were formed primarily as a fighting force, and after an initial logistically catastrophic raid, were teamed up with the LRDG. The LRDG were a self-sufficient unit with their own procurement, workshops, maps, navigation, radios, armament, planes and reported directly to the Commander in Chief Middle East. This provided the SAS with the resources they lacked, gave them transport, and let them concentrate on creating havoc hundreds of miles behind the enemy’s front lines. This was highly effective, although it conflicted with the LRDG low profile intelligence gathering, and eventually the SAS acquired their own transport and became a separate unit.

Whilst the Italians vastly outnumbered the British, they had no stomach for fighting. But they did have an Auto Saharan force, unlike the Germans, who were only capable of fighting in a regimental fashion and had no equivalent units.

The LRDG were not a formal unit in that they had little regimentation and virtually no army issue equipment. They had bought and converted their own trucks, begged borrowed and stole equipment including from the enemy, had their own support planes and heavy supply section, no formal uniform apart from the Scorpion badge on whatever clothing was appropriate to conditions, and no drills or inspections. They did however run their own vigorous training regime, especially in desert navigation by sun or stars. After weeks in the desert a returning unit would be greeted with much suspicion by other soldiers, unwashed and unshaven, they more resembled a band of motorised marauding Arabs than a British elite force.

Their vehicles were unmarked, enabling them to offer a friendly wave to enemy fighters who often mistook them for their own forces, the disadvantage being they were sometimes strafed by the RAF. Occasionally they would venture on to main roads, offering a salute to passing enemy vehicles, and with Italian or German speaking comrades even bluffing their way through enemy roadblocks.

My Uncle, James Wilson, Scots Guards attached to LRDG, Corporal, acting Sergeant, joined in 1940. His parent unit was 2 Battalion Scots Guards. Born 14/9/1919.

There follows some brief highlights in a timeline of desert exploits:

1938 The 2nd Battalion Scots Guards were stationed at Kasr-el-nil Barracks in Cairo. By the end of 1940 they had seen no action, and some were eager to represent their Regiment facing the enemy. The chance to join a fighting unit for some offered an opportunity not to be missed.

1940

July 10th LRDG formed, with Major Ralph A Bagnold as CO

Sept First Patrol of New Zealanders

T, R, & W Patrols, all New Zealanders

On one occasion, unable to get near enough to observe an Italian garrison by vehicle, Captain Pat Clayton put two Arabs and a camel in a lorry and drove them across the desert so they could carry out recognisance un-detected.

First encounter with Italian forces captured a convoy with 2500 gallons of petrol, official war mail, supplies, 7 prisoners and a goat, which surprised the Italians somewhat as they were 650 miles behind their front line.

Italian offensive of 250,000 troops halted amid confusion of attacks on their southern flank supply line by LRDG.

Nov Expanded to 6 patrols, each with 2 officers & 28 other ranks

Dec G Patrol formed from Coldstream & 2nd Battalion Scots Guards under Captain Pat Clayton / Major Crichton-Stuart, comprising 31 NCO’s and Guardsmen. Initially 18 were recruited from each regiment, all volunteers, into what was then an unknown secret unit. (It is interesting that they volunteered only knowing it was a fighting unit, nothing else - whereas in just a few months their exploits became legend and every fighting mans dream unit).

Boxing Day left for Murzuk Raid with 76 men of G & T Patrols plus 10 French and 23 vehicles. Murzuk was an Italian Fort with a garrison of 200 and an airdrome 1000 miles from Cairo but requiring a 1500-mile journey taking 18 days.

1941

David Stirling, Scots Guards, founded the Special Air Service.

Jan LRDG carried out Murzuk Raid on Jan 11th. Two were killed, three shot below the knee, and Guardsman Sgt Wilson incurred a severe leg wound. He was carried by truck to Zouar, via further missions at Treghen, Gatrun & Abd El Galil, arriving on the 20th, then flown to Fort Lany with Bagnold, then Khartoum, having travelled 3000 miles in 16 days to reach the General Hospital in Cairo. It was reported he ‘had survived the shocking journey from Murzuk with admirable fortitude’ and ‘made a good recovery’.

It transpired afterwards that a Frenchman had also been shot in the calf but had just cauterised it with his cigarette and carried on fighting, afterwards he ‘had not bothered’ to see the Doctor.

At Gebel Sherif on Jan 31st Clayton with T Patrol was attacked by 5 Italian cars and 3 aircraft. Clayton was wounded and captured.

Four men presumed killed when their truck exploded had survived and were unknowingly left behind. 1 was wounded in the foot, another in the throat, and only had 14 pints of water between them. They decided to walk back to base, some giving up on the way, but later found although one died. After 10 days the last one was found, Moore, still walking, having covered 210 miles, and was somewhat annoyed as he had wanted to finish the last 80 miles on his own.

Mar Added Y & S Patrols – Southern Rhodesians

Aug Guy Prendergast became CO

Sept Trial road watch on enemy coast road 400 miles behind the front line, but a 600-mile journey from the LRDG base.

Oct T1 Patrol captured two German trucks 50 miles outside of Benghazi, this time the Germans being surprised as they were 500 miles behind their front line at Sollum.

Nov Started road watch to Spring 1942.

S1 Patrol captured a lorry full of Italians, including by chance a Regia Aeronutica pilot who had previously attacked the LRDG. The Italians were, as always, surprised as they were 500 miles from the nearest British position.

Dec The SAS, deployed by the LRDG, were inflicting as much damage on the Luftwaffe as the RAF.

1942

Comprised 25 officers and 278 other ranks

Jan 9 men had their truck destroyed by Stukas, had to spend 8 days walking 200 miles over desert with little water to get to an oasis

Feb G Patrol split, Lieutenant Robin Gurdon commanded G2, Alastair Timpson G1

Mar G2 Jebel road watch carried out with Sgt Wilson, involving a trek of over 60 miles with heavy equipment.

Spring through to December carried out 24-hour Road Watches with 5.00am to 7.00pm day shifts of two soldiers hidden by the roadside.

Involved a week at a time 600 miles from their base.

May Lieutenant Robin Gurdon left Siwa with G2 headed to Benghazi with David Stirling.

On the 21st David Stirling with 5 others (including Randolph Churchill) spent 24 hours carrying out an attack on Benghazi using a British Ford Staff Car 200 miles behind the enemy front line, passing through an Italian roadblock twice.

G1 and T2 were tasked with blowing up enemy trucks on the coast road, without the enemy knowing how that was being done. It was decided to use time bombs thrown into passing trucks. The trouble was the enemy trucks were moving too fast, so they erected German road works to slow them down. This still proved impossible, so Timpson decided to drive a truck without lights behind an enemy vehicle, with Sergeant Fraser sat on the bonnet to lob a time bomb in the back. Unfortunately they came upon a broken down Italian lorry who asked them for a tow, thinking they must be Germans, before they could implement their plan. The impossible had become unbelievable!

July Gurdon and Stirling headed to attack an enemy base and airfield respectively.

Attacked by 3 Italian fighters on way to attack airfield between Fuka and Daba with SAS, Robin Gurdon fatally wounded, attended by his Patrol Sgt Wilson, remaining with him exposed to heavy fire from enemy fighter aircraft. Murrey his driver was severely wounded. The mission was aborted but Gurdon died the following day. Lieutenant Sweeting later took command of G2. Wilson was described as Gunner & Medical Orderly.

85 enemy aircraft destroyed by SAS & LRDG near Fuka & Baggush.

After T Patrol and the SAS attacked one airfield the Germans pursued and attacked the Patrol directed by an aircraft, the aircraft frequently landing to confer with the German troops. Two New Zealanders from T Patrol got fed up with this so followed the plane and next time it landed they shot it up and burnt it.

Sept Failed raid on Tobruk.

Eight German Heinkel’s attacked the LRDG base at Kufra, the LRDG & SAS armed with captured Italian Breda 20mm guns, shot five down.

1943

Italians and Germans in retreat.

February Hons was the new base for the LRDG. G1 and G2 patrols had been decimated in action and was reconstructed into a single G patrol. Three veterans from Murzuk remained, including sergeant Wilson, plus another 14 new recruits mostly Guards. G Patrol was now under Bruce and sent on a scouting patrol around Chott Djerid. This was the last LRDG patrol, covering 3500 miles in 37 days, and was not without incident.

After the patrol they went to Constantine and stopped in Biskra on their way. This was full of fresh American troops yet to see desert or battle. The LRDG were the Yanks first contact with the British 8th Army. Reported at the time as ‘Ay-rabs in Jeeps’, large bearded men in Arab headdress driving desert camouflaged vehicles bristling with guns - not something even encountered in Hollywood movies!

May North Africa under Allied control, Rommel defeated

1947 SAS reformed

Credits:

G Patrol, 1958, Michael Crichton-Stuart

Sergeant Kevin Gorman, Scots Guards Archive

The desert war ran from December 1940 to March 1943 and was the place the Germans and Italians were first defeated.

Patrols were designed with a 1500-mile capability & over 25 days supplies, although it was common to double this.

Despite being a secret clandestine group, its reputation was such that there was never any shortage of volunteers, just the difficulty of finding the right ones. At one point 12 recruits were taken from 700 volunteers and on another 20 were taken from 500 interviewed.

One recruit, arriving on Christmas Day, was found unsuitable, and at 7.30am on Boxing Day found to his dismay he was on his way back to his original unit.

Their prime directive was to gather intelligence about enemy movements hundreds of miles behind the front lines without their presence being known, but they were also involved in frequent attacks on enemy airfields and garrisons, appearing from nowhere and melting away afterwards. They often appeared to be a bigger force than they were, confusing the enemy as to a major offensive, and causing them to deploy valuable resources to guarding their long supply lines.

They numbered just 90 at the start, rising to around 350, including support staff. As they went about exploring uncharted deserts, they produced the first detailed maps, and latterly found routes to outflank Rommel and literally led the eighth army units through previously impassable terrain in pincer movements around German defences.

The LRDG were the first special forces unit, later followed by the SAS. The SAS were formed primarily as a fighting force, and after an initial logistically catastrophic raid, were teamed up with the LRDG. The LRDG were a self-sufficient unit with their own procurement, workshops, maps, navigation, radios, armament, planes and reported directly to the Commander in Chief Middle East. This provided the SAS with the resources they lacked, gave them transport, and let them concentrate on creating havoc hundreds of miles behind the enemy’s front lines. This was highly effective, although it conflicted with the LRDG low profile intelligence gathering, and eventually the SAS acquired their own transport and became a separate unit.

Whilst the Italians vastly outnumbered the British, they had no stomach for fighting. But they did have an Auto Saharan force, unlike the Germans, who were only capable of fighting in a regimental fashion and had no equivalent units.

The LRDG were not a formal unit in that they had little regimentation and virtually no army issue equipment. They had bought and converted their own trucks, begged borrowed and stole equipment including from the enemy, had their own support planes and heavy supply section, no formal uniform apart from the Scorpion badge on whatever clothing was appropriate to conditions, and no drills or inspections. They did however run their own vigorous training regime, especially in desert navigation by sun or stars. After weeks in the desert a returning unit would be greeted with much suspicion by other soldiers, unwashed and unshaven, they more resembled a band of motorised marauding Arabs than a British elite force.

Their vehicles were unmarked, enabling them to offer a friendly wave to enemy fighters who often mistook them for their own forces, the disadvantage being they were sometimes strafed by the RAF. Occasionally they would venture on to main roads, offering a salute to passing enemy vehicles, and with Italian or German speaking comrades even bluffing their way through enemy roadblocks.

My Uncle, James Wilson, Scots Guards attached to LRDG, Corporal, acting Sergeant, joined in 1940. His parent unit was 2 Battalion Scots Guards. Born 14/9/1919.

There follows some brief highlights in a timeline of desert exploits:

1938 The 2nd Battalion Scots Guards were stationed at Kasr-el-nil Barracks in Cairo. By the end of 1940 they had seen no action, and some were eager to represent their Regiment facing the enemy. The chance to join a fighting unit for some offered an opportunity not to be missed.

1940

July 10th LRDG formed, with Major Ralph A Bagnold as CO

Sept First Patrol of New Zealanders

T, R, & W Patrols, all New Zealanders

On one occasion, unable to get near enough to observe an Italian garrison by vehicle, Captain Pat Clayton put two Arabs and a camel in a lorry and drove them across the desert so they could carry out recognisance un-detected.

First encounter with Italian forces captured a convoy with 2500 gallons of petrol, official war mail, supplies, 7 prisoners and a goat, which surprised the Italians somewhat as they were 650 miles behind their front line.

Italian offensive of 250,000 troops halted amid confusion of attacks on their southern flank supply line by LRDG.

Nov Expanded to 6 patrols, each with 2 officers & 28 other ranks

Dec G Patrol formed from Coldstream & 2nd Battalion Scots Guards under Captain Pat Clayton / Major Crichton-Stuart, comprising 31 NCO’s and Guardsmen. Initially 18 were recruited from each regiment, all volunteers, into what was then an unknown secret unit. (It is interesting that they volunteered only knowing it was a fighting unit, nothing else - whereas in just a few months their exploits became legend and every fighting mans dream unit).

Boxing Day left for Murzuk Raid with 76 men of G & T Patrols plus 10 French and 23 vehicles. Murzuk was an Italian Fort with a garrison of 200 and an airdrome 1000 miles from Cairo but requiring a 1500-mile journey taking 18 days.

1941

David Stirling, Scots Guards, founded the Special Air Service.

Jan LRDG carried out Murzuk Raid on Jan 11th. Two were killed, three shot below the knee, and Guardsman Sgt Wilson incurred a severe leg wound. He was carried by truck to Zouar, via further missions at Treghen, Gatrun & Abd El Galil, arriving on the 20th, then flown to Fort Lany with Bagnold, then Khartoum, having travelled 3000 miles in 16 days to reach the General Hospital in Cairo. It was reported he ‘had survived the shocking journey from Murzuk with admirable fortitude’ and ‘made a good recovery’.

It transpired afterwards that a Frenchman had also been shot in the calf but had just cauterised it with his cigarette and carried on fighting, afterwards he ‘had not bothered’ to see the Doctor.

At Gebel Sherif on Jan 31st Clayton with T Patrol was attacked by 5 Italian cars and 3 aircraft. Clayton was wounded and captured.

Four men presumed killed when their truck exploded had survived and were unknowingly left behind. 1 was wounded in the foot, another in the throat, and only had 14 pints of water between them. They decided to walk back to base, some giving up on the way, but later found although one died. After 10 days the last one was found, Moore, still walking, having covered 210 miles, and was somewhat annoyed as he had wanted to finish the last 80 miles on his own.

Mar Added Y & S Patrols – Southern Rhodesians

Aug Guy Prendergast became CO

Sept Trial road watch on enemy coast road 400 miles behind the front line, but a 600-mile journey from the LRDG base.

Oct T1 Patrol captured two German trucks 50 miles outside of Benghazi, this time the Germans being surprised as they were 500 miles behind their front line at Sollum.

Nov Started road watch to Spring 1942.

S1 Patrol captured a lorry full of Italians, including by chance a Regia Aeronutica pilot who had previously attacked the LRDG. The Italians were, as always, surprised as they were 500 miles from the nearest British position.

Dec The SAS, deployed by the LRDG, were inflicting as much damage on the Luftwaffe as the RAF.

1942

Comprised 25 officers and 278 other ranks

Jan 9 men had their truck destroyed by Stukas, had to spend 8 days walking 200 miles over desert with little water to get to an oasis

Feb G Patrol split, Lieutenant Robin Gurdon commanded G2, Alastair Timpson G1

Mar G2 Jebel road watch carried out with Sgt Wilson, involving a trek of over 60 miles with heavy equipment.

Spring through to December carried out 24-hour Road Watches with 5.00am to 7.00pm day shifts of two soldiers hidden by the roadside.

Involved a week at a time 600 miles from their base.

May Lieutenant Robin Gurdon left Siwa with G2 headed to Benghazi with David Stirling.

On the 21st David Stirling with 5 others (including Randolph Churchill) spent 24 hours carrying out an attack on Benghazi using a British Ford Staff Car 200 miles behind the enemy front line, passing through an Italian roadblock twice.

G1 and T2 were tasked with blowing up enemy trucks on the coast road, without the enemy knowing how that was being done. It was decided to use time bombs thrown into passing trucks. The trouble was the enemy trucks were moving too fast, so they erected German road works to slow them down. This still proved impossible, so Timpson decided to drive a truck without lights behind an enemy vehicle, with Sergeant Fraser sat on the bonnet to lob a time bomb in the back. Unfortunately they came upon a broken down Italian lorry who asked them for a tow, thinking they must be Germans, before they could implement their plan. The impossible had become unbelievable!

July Gurdon and Stirling headed to attack an enemy base and airfield respectively.

Attacked by 3 Italian fighters on way to attack airfield between Fuka and Daba with SAS, Robin Gurdon fatally wounded, attended by his Patrol Sgt Wilson, remaining with him exposed to heavy fire from enemy fighter aircraft. Murrey his driver was severely wounded. The mission was aborted but Gurdon died the following day. Lieutenant Sweeting later took command of G2. Wilson was described as Gunner & Medical Orderly.

85 enemy aircraft destroyed by SAS & LRDG near Fuka & Baggush.

After T Patrol and the SAS attacked one airfield the Germans pursued and attacked the Patrol directed by an aircraft, the aircraft frequently landing to confer with the German troops. Two New Zealanders from T Patrol got fed up with this so followed the plane and next time it landed they shot it up and burnt it.

Sept Failed raid on Tobruk.

Eight German Heinkel’s attacked the LRDG base at Kufra, the LRDG & SAS armed with captured Italian Breda 20mm guns, shot five down.

1943

Italians and Germans in retreat.

February Hons was the new base for the LRDG. G1 and G2 patrols had been decimated in action and was reconstructed into a single G patrol. Three veterans from Murzuk remained, including sergeant Wilson, plus another 14 new recruits mostly Guards. G Patrol was now under Bruce and sent on a scouting patrol around Chott Djerid. This was the last LRDG patrol, covering 3500 miles in 37 days, and was not without incident.

After the patrol they went to Constantine and stopped in Biskra on their way. This was full of fresh American troops yet to see desert or battle. The LRDG were the Yanks first contact with the British 8th Army. Reported at the time as ‘Ay-rabs in Jeeps’, large bearded men in Arab headdress driving desert camouflaged vehicles bristling with guns - not something even encountered in Hollywood movies!

May North Africa under Allied control, Rommel defeated

1947 SAS reformed

Credits:

G Patrol, 1958, Michael Crichton-Stuart

Sergeant Kevin Gorman, Scots Guards Archive

Members of G Patrol after their formation in late 1940, possibly on their way to attack Murzuk.

The Long Range Desert Group members were the brains behind the SAS. Centre of the picture is my uncle Jim Wilson.

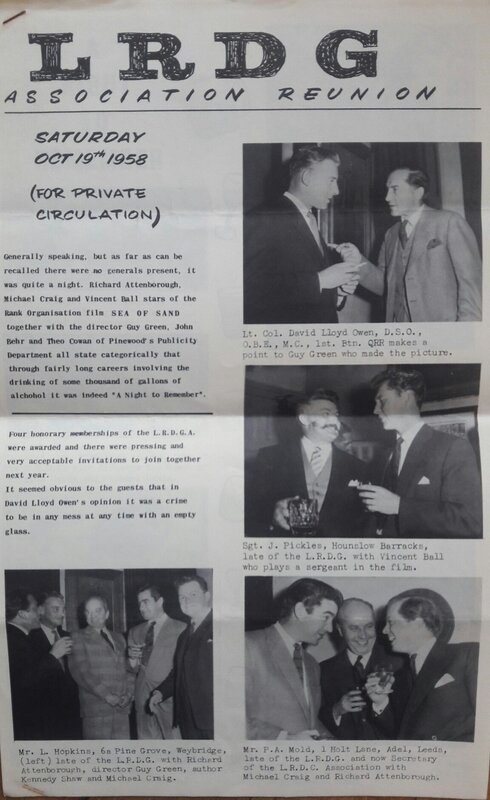

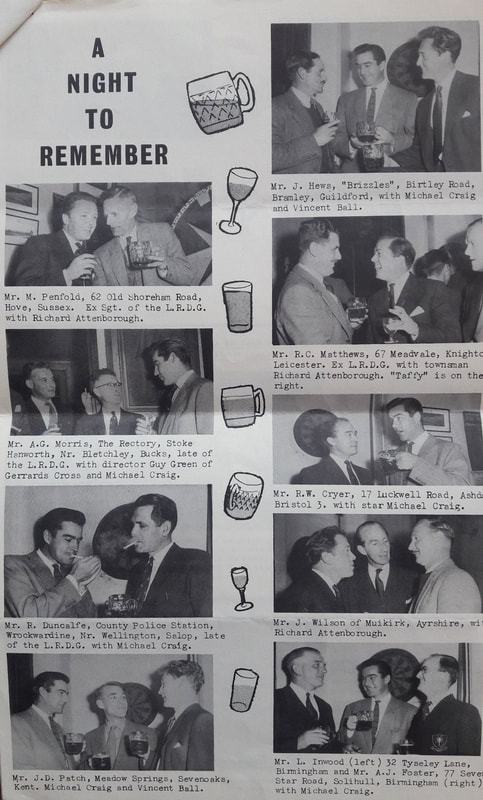

Sea of Sand 1958

An article on the premier of the film Sea of Sand about the LRDG. Just 17 of the original members were invited guests. Jim Wilson in photo towards bottom right.

Mail Online Article

Written by REBECCA TAYLOR FOR MAILONLINE

PUBLISHED: 13:25, 13 April 2017

The men of the Long Range Desert Group carried out clandestine operations deep behind enemy lines in the Second World War and were the 'brains' behind the SAS.

They also launched hit-and-run raids and gathered intelligence on German and Italian targets.

They carried out numerous missions in tandem with the SAS, using their unparalleled knowledge of the treacherous Sahara desert to guide the elite unit to enemy airfields where attacks would be launched.

The group traversed huge areas of the Sahara that had never been explored by Europeans before, and their information gathering was so important to success in North Africa that General Bernard Montgomery said without them operations would have been 'a leap in the dark'.

Now, photographs of the men have been released in a new book. 21

One memorable photo is a highly symbolic image of a soldier with his foot on the head of a bust of Mussolini as the Allies began liberating western Libya from Italian rule.

Another remarkable image is of a member of the Long Range Desert Group perched precariously on top of a palm tree from where he carried out reconnaissance.

There are striking images of sandstorms, tanks driving through the desert and a wounded soldier waiting to be flown to hospital.

What the images reveal is the close bond that existed between the members of the unit whose diligence dovetailed perfectly with the superior firepower of the SAS to defeat the enemy.

Cameras were banned so the soldier who took the fascinating photos did so without the authority of his senior officers.

With the surrender of the Axis forces in Tunisia in May 1943, the Long Range Desert Group moved operations to the eastern Mediterranean, carrying out missions in the Greek islands, Italy and the Balkans where they operated in boats, on foot and by parachute.

The short-lived unit - which never numbered more than 350 men - was disbanded in August 1945 after the War Office decided against transferring them to the Far East to conduct operations against the Japanese Empire.

In his book, historian Gavin Mortimer has interviewed surviving veterans and gained special access to the SAS archives to tell the story of the origins and dramatic operations of the unit.

The Long Range Desert Group was the brainchild of a contemporary of Lawrence of Arabia, scientist and soldier Major Ralph Bagnold, who insisted men on the ground were needed to carry out crucial reconnaissance missions which he felt were not possible by air.

They were established almost a year and a half before the SAS were formed in November 1941 making them the first ever special forces unit.

At first the Long Range Desert Group was made up of soldiers from New Zealand since Maj Bagnold was impressed by their 'speed and thoroughness' in adjusting to the extreme desert conditions.

In time, the unit would incorporate soldiers from Britain and Southern Rhodesia.

The extraordinary men of the unit would stay hidden concealed in bushes or ditches for days at a time just yards from German and Italian forces observing the enemy's every move and relaying that valuable information via radio to the SAS.

Mr Mortimer, 46, who lives in Paris, said: 'The Long Range Desert Group was actually established before the SAS and for the war-time generation they were more famous than them.

'It was only the Iranian siege of 1980 which propelled the SAS into public consciousness.

'The Long Range Desert Group disbanded at the end of the war and they have been lost to history so this book is really to make people aware of the importance and contribution of that unit to the Second World War.

'They were the brains of the operation in the desert while the SAS were the brawn. It was their role to navigate them to their targets.

'I believe the Long Range Desert Group were more important and valuable to the winning of the war in North Africa than the SAS.

They would drop deep behind enemy lines and their surveillance was crucial as they reported back to General Montgomery the strength of the Germans and where to attack them.

'They were the eyes and ears of the offensive. What they did was painstaking - they would spend days hidden just yards from the main coastal road which the Germans would use.

'They would take notes of how many vehicles passed, how many soldiers there were and even the mood of the soldiers - if they were singing or depressed - and this information would be radioed back.

'Personnel would work in pairs sometimes hidden in a bush or concealed in a drop in the ground. They would camouflage themselves and observe using binoculars.

'When night came, they would hurry back to their patrol a mile or two further into the desert and would radio in all the information.

'There were very narrow escapes. Once a German convoy camped just yards from where a couple of men were hiding and one of the soldiers wandered over and relieved himself in the bush they were concealed in.

'I began my research three years ago and there were still 15 veterans from the Long Range Desert Group. Now that number is six or seven.

'I was able to speak to some veterans who have never spoken publicly about their experiences before now. They are such a modest generation but what they did took extraordinary discipline and courage.'

The Long Range Desert Group in World War II is written by Gavin Mortimer and costs £25

THE AFRICAN CAMPAIGN IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR

The North African campaign began in June 1940 and lasted for three years. Allied and Axis forces pushed one another back across the Sahara.

At this point, the Allies consisted predominantly of British, French and British Indian forces, with the Axis countries being Germany, Japan and Italy.

The Allies had the back up of American forces in North Africa from 1942.

Although both sides had former colonial interests in the region, the Axis aims were around denying the Allies access to Middle Eastern oil supplies and cutting Britain off from the network it had in North Africa.

In three phases, the campaign covered western Egypt and eastern Libya (the Western desert campaign), Algeria and Morocco (Operation Torch) and Tunisia (the Tunisia campaign).

The skirmishes started almost as soon as war was declared, with Italian forces invaded Egypt in September 1940 and British forces responded in December.

There were numerous pushes back and forth, but the Second Battle of El Alamein in late 1942 is regarded as a turning point, when the British army drove Axis troops all the way back through Libya.

Operation Torch of November 1942 brought in thousands of British and American troops, flushing out remaining Axis troops from Tunisia and bringing the campaign to an end.

Throughout the entire three year campaign, Germans and Italians suffered 620,000 casualties, while the British Commonwealth lost 220,000 men. Nearly 900,000 German and Italian troops were killed or 'neutralised' in the conflict.

Allied victory in North Africa allowed the invasion of Italy in 1943.

Sources: The Atlantic and USHMM

PUBLISHED: 13:25, 13 April 2017

The men of the Long Range Desert Group carried out clandestine operations deep behind enemy lines in the Second World War and were the 'brains' behind the SAS.

They also launched hit-and-run raids and gathered intelligence on German and Italian targets.

They carried out numerous missions in tandem with the SAS, using their unparalleled knowledge of the treacherous Sahara desert to guide the elite unit to enemy airfields where attacks would be launched.

The group traversed huge areas of the Sahara that had never been explored by Europeans before, and their information gathering was so important to success in North Africa that General Bernard Montgomery said without them operations would have been 'a leap in the dark'.

Now, photographs of the men have been released in a new book. 21

One memorable photo is a highly symbolic image of a soldier with his foot on the head of a bust of Mussolini as the Allies began liberating western Libya from Italian rule.

Another remarkable image is of a member of the Long Range Desert Group perched precariously on top of a palm tree from where he carried out reconnaissance.

There are striking images of sandstorms, tanks driving through the desert and a wounded soldier waiting to be flown to hospital.

What the images reveal is the close bond that existed between the members of the unit whose diligence dovetailed perfectly with the superior firepower of the SAS to defeat the enemy.

Cameras were banned so the soldier who took the fascinating photos did so without the authority of his senior officers.

With the surrender of the Axis forces in Tunisia in May 1943, the Long Range Desert Group moved operations to the eastern Mediterranean, carrying out missions in the Greek islands, Italy and the Balkans where they operated in boats, on foot and by parachute.

The short-lived unit - which never numbered more than 350 men - was disbanded in August 1945 after the War Office decided against transferring them to the Far East to conduct operations against the Japanese Empire.

In his book, historian Gavin Mortimer has interviewed surviving veterans and gained special access to the SAS archives to tell the story of the origins and dramatic operations of the unit.

The Long Range Desert Group was the brainchild of a contemporary of Lawrence of Arabia, scientist and soldier Major Ralph Bagnold, who insisted men on the ground were needed to carry out crucial reconnaissance missions which he felt were not possible by air.

They were established almost a year and a half before the SAS were formed in November 1941 making them the first ever special forces unit.

At first the Long Range Desert Group was made up of soldiers from New Zealand since Maj Bagnold was impressed by their 'speed and thoroughness' in adjusting to the extreme desert conditions.

In time, the unit would incorporate soldiers from Britain and Southern Rhodesia.

The extraordinary men of the unit would stay hidden concealed in bushes or ditches for days at a time just yards from German and Italian forces observing the enemy's every move and relaying that valuable information via radio to the SAS.

Mr Mortimer, 46, who lives in Paris, said: 'The Long Range Desert Group was actually established before the SAS and for the war-time generation they were more famous than them.

'It was only the Iranian siege of 1980 which propelled the SAS into public consciousness.

'The Long Range Desert Group disbanded at the end of the war and they have been lost to history so this book is really to make people aware of the importance and contribution of that unit to the Second World War.

'They were the brains of the operation in the desert while the SAS were the brawn. It was their role to navigate them to their targets.

'I believe the Long Range Desert Group were more important and valuable to the winning of the war in North Africa than the SAS.

They would drop deep behind enemy lines and their surveillance was crucial as they reported back to General Montgomery the strength of the Germans and where to attack them.

'They were the eyes and ears of the offensive. What they did was painstaking - they would spend days hidden just yards from the main coastal road which the Germans would use.

'They would take notes of how many vehicles passed, how many soldiers there were and even the mood of the soldiers - if they were singing or depressed - and this information would be radioed back.

'Personnel would work in pairs sometimes hidden in a bush or concealed in a drop in the ground. They would camouflage themselves and observe using binoculars.

'When night came, they would hurry back to their patrol a mile or two further into the desert and would radio in all the information.

'There were very narrow escapes. Once a German convoy camped just yards from where a couple of men were hiding and one of the soldiers wandered over and relieved himself in the bush they were concealed in.

'I began my research three years ago and there were still 15 veterans from the Long Range Desert Group. Now that number is six or seven.

'I was able to speak to some veterans who have never spoken publicly about their experiences before now. They are such a modest generation but what they did took extraordinary discipline and courage.'

The Long Range Desert Group in World War II is written by Gavin Mortimer and costs £25

THE AFRICAN CAMPAIGN IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR

The North African campaign began in June 1940 and lasted for three years. Allied and Axis forces pushed one another back across the Sahara.

At this point, the Allies consisted predominantly of British, French and British Indian forces, with the Axis countries being Germany, Japan and Italy.

The Allies had the back up of American forces in North Africa from 1942.

Although both sides had former colonial interests in the region, the Axis aims were around denying the Allies access to Middle Eastern oil supplies and cutting Britain off from the network it had in North Africa.

In three phases, the campaign covered western Egypt and eastern Libya (the Western desert campaign), Algeria and Morocco (Operation Torch) and Tunisia (the Tunisia campaign).

The skirmishes started almost as soon as war was declared, with Italian forces invaded Egypt in September 1940 and British forces responded in December.

There were numerous pushes back and forth, but the Second Battle of El Alamein in late 1942 is regarded as a turning point, when the British army drove Axis troops all the way back through Libya.

Operation Torch of November 1942 brought in thousands of British and American troops, flushing out remaining Axis troops from Tunisia and bringing the campaign to an end.

Throughout the entire three year campaign, Germans and Italians suffered 620,000 casualties, while the British Commonwealth lost 220,000 men. Nearly 900,000 German and Italian troops were killed or 'neutralised' in the conflict.

Allied victory in North Africa allowed the invasion of Italy in 1943.

Sources: The Atlantic and USHMM

The Men Who Saved the SAS: Major Ralph Bagnold and the Long Range Desert Group

27th November 2017 By Gavin Mortimer

Ralph Bagnold was as unlikely a special forces commander as anyone could imagine. His war had been the Great War, when as a junior signals officer he had survived the carnage of the Western Front. When World War II began in September 1939, Bagnold was 43 and earning a comfortable living as a scientist and writer.

Recalled to the colours four years after he had retired from the army, Major Bagnold was posted to Officer Commanding, East Africa Signals, and dispatched on a troopship to Kenya. But he never arrived. In early October, Bagnold’s vessel, RMS Franconia, collided with a merchant cruiser in the Mediterranean. He and the rest of his troop transferred to another vessel and sailed to Port Said in Egypt to await the first available ship to Kenya.

Bagnold was delighted. Egypt was a country he knew well, better in fact than nearly any other Briton. He had spent most of the 1920s in Egypt with his regiment, entranced by the culture and the vast desert that stretched west into Libya. In 1927, he made his first foray into the Libyan desert, leading a small band of explorers in a fleet of Model T Fords. More expeditions followed, penetrating farther into the desert’s brutal interior than any other European had. Bagnold’s fascination was as much motivated by science as by exploration, and he began studying the terrain, leading him to publish the critically acclaimed The Physics of Blown Sand And Desert Dunes in 1939.

Back in Egypt, Bagnold took the train from Port Said to Cairo to look up old friends. He dined with one such acquaintance in the restaurant of the exclusive Shepheard’s Hotel, where he was spotted by the gossip columnist of The Egyptian Gazettenewspaper. A few days later, the word was out that Bagnold was back in town, and within a matter of days he was summoned to the office of General Archibald Wavell, General Officer Commanding-in-Chief of Middle East Command.

Wavell pumped Bagnold for information on the accessibility of the Libyan Desert – the general was increasingly concerned by intelligence reports that the Italians had as many as 250,000 men in 15 divisions under Marshal Rodolfo Graziani. So impressed was he by what Bagnold told him that Wavell arranged for his permanent transfer to North Africa.

General Sir Archibald Wavell, Commander-in-Chief Middle East, at his desk, 15 August 1940. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205193528Bagnold’s vision brought to lifeBagnold was sent to Mersa Matruh – 135 miles west of Cairo – where he discovered that the most up-to-date map the British forces possessed of Libya dated from 1915. He was similarly appalled by the indifference of senior officers to the threat posed by the Italians – they believed the enemy would make a full-frontal attack on Mersa Matruh, which they would easily repel, but Bagnold suspected the Italians, some of whom he had encountered during his expeditions of the 1920s, would launch surprise attacks on British positions in Egypt from further south.

Bagnold’s idea was to form a small reconnaissance force to patrol the 700-mile frontier with Libya. This was rejected, as it was when he submitted it again in January 1940, and the following month Bagnold was posted as a military advisor to Turkey, presumably to give Middle East Headquarters (MEHQ) in Cairo some peace and quiet.

But Bagnold wouldn’t give up, and after Italy declared war on Britain on 10 June 1940, he tried for a third time to convince the top brass of his idea, explaining in an additional paragraph that there would be three patrols:

“Every vehicle of which, with a crew of three and a machine gun, was to carry its own supplies of food and water for three weeks, and its own petrol for 2,500 miles of travel across average soft desert surface… [each] patrol to carry a wireless set, navigating and other equipment, medical stores, spare parts and further tools.”

This time Bagnold entrusted his friend, Brigadier Dick Baker, to ensure the proposal was put directly into the hands of Wavell. Baker obliged and within four days of receiving Bagnold’s proposition, Wavell had authorised him to form the new unit, provisionally entitled the Long Range Patrol (LRP).

Wavell was a hard taskmaster, however, giving Bagnold just six weeks to make his vision a reality. Men, equipment, rations, weapons, vehicles… it was a formidable challenge but one that Bagnold rose to. First, he searched for the soldiers; he tracked down most of his old companions from his exploration days, and while one or two were unable to secure a release from their military duty, Bagnold was soon joined in Cairo by Bill Kennedy-Shaw and Pat Clayton, who by 1940 had accumulated nearly 20 years of experience with the Egyptian Survey Department. Also recruited to the new unit was captain Teddy Mitford, a relative of the infamous sisters and a desert explorer in his own right during the late 1930s.

While Clayton, Mitford and Kennedy-Shaw started to hunt down the necessary equipment, Bagnold flew to Palestine on 29 June to see Lt-General Thomas Blamey, commander of the Australian Corps. Bagnold requested permission to recruit 80 Australian soldiers, explaining that in his view Australians would be the Allied soldiers most likely to adapt quickest to desert reconnaissance. Blamey, on the orders of his government, refused, so Bagnold turned to the New Zealand forces in Egypt.

This time he met with success, and 80 officers, non-commissioned officers and men from the New Zealand Divisional Cavalry Regiment and Machine-Gun Battalion volunteered to be part of the LRP. Bagnold took an instant shine to the Kiwis, saying:

“They made an impressive party by English standards. Tougher and more weather-beaten in looks, a sturdy basis of sheep-farmers, leavened by technicians, property-owners and professional men, and including a few Maoris. Shrewd, dry-humoured, curious of every new thing, and quietly thrilled when I told them what we were to do.”

July was spent assembling the vehicles and equipment and training the New Zealanders in the rudiments of desert motoring and navigation. Kennedy-Shaw, appointed the unit’s intelligence officer, told the Kiwis that the Libyan Desert measured 1,200 miles by 1,000 – or put another way, was roughly the size of India. It was bordered by the Nile in the east and the Mediterranean in the north. In the south, which was limestone compared to the sandstone in the north, the desert extended as far as the Tibesti Mountains, while the political frontier with Tunisia and Algeria marked its western limits.

A well-loaded Chevrolet truck about to set off on patrol from Siwa. This vehicle was crewed by New Zealanders, many of whom joined the Long Range Desert Group in 1940 from a consignment of troops who found themselves at Alexandria without their arms and equipment, which had been lost at sea. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205125571The unit proves its worthBy the first week of August 1940, the unit was ready for its first patrol and the honour fell to 44-year-old Captain Pat Clayton. He and his small hand-picked party of seven left Cairo in two Chevrolet trucks. Crossing the border into Libya, they continued on to Siwa Oasis, where Alexander the Great had led his army in 332 BCE. “The little patrol of two cars then struck due west, exploring, and made the unwelcome discovery of a large strip of sand sea between the frontier and the Jalo-Kufra road,” wrote Clayton in his subsequent report. “The Chevrolet clutches began to smell a bit by the time we got across, but the evening saw us near the Kufra track.”

They laid up here for three days, taking great care to conceal their presence from the Italians, as they observed the track for signs of activity. They returned to Cairo on 19 August, having covered 1,600 miles of the barren desert in 13 days.

Clayton and Bagnold reported their findings to General Wavell, who, having heard an account of the unit’s first patrol, “made up his mind then and there to give us his strongest backing.” A week later, Wavell inspected the LRP and told them he had informed the War Office they “were ready to take the field.”

Bagnold split the LRP into three patrols, assigning to each a letter of no particular significance. Captain Teddy Mitford commanded W Patrol, Captains Pat Clayton and Bruce Ballantyne (a New Zealander) were the officers in charge of T Patrol and Captain Don Steele, a New Zealand farmer from Takapu, led R Patrol. Each patrol consisted of 25 other ranks, transported in ten 30-cwt Chevrolet trucks and a light 15-cwt pilot car. They carried rations and equipment to sustain them over 1,500 miles and for armament each patrol possessed a 3.7mm Bofors gun, four Boys AT (anti-tank) rifles and 15 Lewis guns.

For the next two months the LRP reconnoitred large swathes of central Libya, often enduring daytime temperatures in excess of 49 degrees Celsius as they probed for signs of Italian troop movements.

On 19 September, Mitford’s patrol encountered two Italian six-ton lorries and opened fire, giving the aristocratic Englishman the honour of blooding the LRP in battle. In truth, it wasn’t much of a battle; the Italians, stunned to meet the enemy so far west, quickly waved a white flag. The prisoners were brought back to Cairo, along with 2,500 gallons of petrol and a bag of official mail.

General Wavell was delighted, not just with the official mail that contained much important intelligence but with the LRP’s work throughout the autumn of 1940. Bagnold capitalised on the praise with a request to expand the unit, suggesting to Wavell that with more men he could strike fear into the Italians by launching a series of hit-and-run attacks across a wide region of Libya. On 22 November, Bagnold was promoted to acting lieutenant-colonel and given permission to form two new patrols and reconstitute the Long Range Patrol as the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG).

For his new recruits, Bagnold turned to the British army and what he considered the cream: the Guards and the Yeomanry Divisions. By the end of December, he had formed G (Guards) Patrol, consisting of 36 soldiers from the 3rd Battalion The Coldstream Guards and the 2nd Battalion The Scots Guards, commanded by Captain Michael Crichton-Stuart. Y Patrol was raised a couple of months later, composed of men from, among others, the Yorkshire Hussars, the North Somerset Yeomanry and the Staffordshire Yeomanry. For their inaugural operation, however, G Patrol was placed under the command of Pat Clayton, whose T Patrol would offer support.

Two Long Range Desert Group patrols meet in the desert. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205194946A successful first missionTheir target was Murzuk, a well-defended Italian fort in south-western Libya, nestled among palm trees with an airfield close by. The fort was approximately 1,000 miles to the west of Cairo as the crow flies, and reaching it entailed a gruelling journey that lasted for a fortnight. There were 76 raiders in all, travelling in 23 vehicles, including nine members of the Free French who had been seconded to the operation in return for flying up additional supplies from their base in Chad.

The raiding party stopped for lunch on 11 January, just a few miles from Murzuk, and finalised their plan for the attack: Clayton’s T Patrol would attack the airfield that lay in close proximity to the fort while G Patrol targeted the actual garrison. Crichton-Stuart recalled that as they neared the fort, they passed a lone cyclist:

“This gentleman, who proved to be the postmaster, was added to the party with his bicycle. As the convoy approached the fort, above the main central tower of which the Italian flag flew proudly, the guard turned out. We were rather sorry for them, but they probably never knew what hit them.”

Opening fire 150 yards from the fort’s main gates, the LRDG force split, with the six trucks of Clayton’s patrol heading towards the airstrip. The terrain was up and down, and the LRDG made use of its undulations to destroy a number of pillboxes scattered about, including an anti-aircraft pit.

Clayton, in the vanguard of the assault, circled a hangar and as he turned the corner, ran straight into a concealed machine gun nest. The Free French officer was shot dead but Clayton soon silenced the enemy position, and by the time his patrol withdrew, they had been responsible for the destruction of three light bombers, a sizeable fuel dump and killed or captured all of the 20 guards.

Meanwhile, G Patrol had subjected the fort to a withering mortar barrage, and after a brief fire fight, the garrison surrendered. Clayton selected two prisoners to bring back to Cairo for interrogation and the rest were left in the shattered remnants of the fort to await the arrival of reinforcements once it was realised the fort’s communications were down.

Headdress worn by a member of the LRDG Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/30103120The Nazis push backFollowing the Allied advance across Libya in the winter of 1940-41, Adolf Hitler had despatched General Erwin Rommel and the Deutsches Afrika Korps to reinforce their Italian allies. The Nazi leader had initially been reluctant to get involved in North Africa, but Admiral Erich Raeder, head of the German navy, warned that if the British maintained their iron grip on the Mediterranean, it would seriously jeopardise his plans for conquest in Eastern Europe.

Rommel wasted little time in attacking the British, launching an offensive on 2 April that ultimately pushed his enemy out of Libya and back into Egypt, right where they had been in 1940. The British managed to hold on to only a couple of footholds in Libya, in the port of Tobruk and 500 miles south in the Oasis of Kufra. On 9 April, Bagnold and most of the LRDG were sent to garrison Kufra, to pass a summer of tedious inactivity that frayed Bagnold’s usually equitable temper. He was also beginning to feel the strain of command, oppressed by the heat and the constant scuttling forth between Cairo and Kufra, and so on 1 August he handed over command of the LRDG to Lt-Colonel Guy Prendergast.

Prendergast had explored the Libyan Desert with Bagnold in the 1920s but had remained in the Royal Tank Regiment. Dour, laconic and precise, Prendergast kept his emotions hidden behind a cool exterior as he did his eyes behind a pair of circular sunglasses. Not to be underestimated, he was innovative, open-minded and a brilliant administrator.

His first challenge as the LRDG’s new commander was to organise five reconnaissance patrols for a new large-scale Allied offensive (codenamed Operation Crusader) on 18 November. The aim of the offensive, planned by General Claude Auchinleck, the successor to the sacked General Wavell, was to retake eastern Libya and its airfields, thereby enabling the RAF to increase its supplies to Malta.

Three Long Range Desert Group 30-cwt Chevrolet trucks, surrounded by desert. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205196758The SAS arriveThe LRDG’s role was the observation and reporting of enemy troop movements, alerting Auchinleck as to what Rommel might be planning in response to the offensive. But they had an additional responsibility: to collect 55 British paratroopers after they’d attacked enemy airfields at Gazala and Tmimi. This small unit had been raised four months earlier by a charismatic young officer called David Stirling and had been designated L Detachment Special Air Service (SAS) Brigade.

Stirling had convinced MEHQ that the enemy was vulnerable to attack along the line of its coastal communications and various aerodromes and supply dumps, by small units of airborne troops attacking not just one target but a series of objectives. Stirling and his men parachuted into Libya on the night of 17 November into what one war correspondent described as “the most spectacular thunderstorm within local memory.” Many of the SAS raiders were injured on landing; others were captured in the hours that followed. The 21 storm-ravaged survivors were eventually rescued by the LRDG and driven to safety, among them a bitterly disappointed Stirling.

It was Lt-Colonel Prendergast who resuscitated the SAS. Receiving an order in late November from MEHQ instructing the LRDG to launch a series of raids against Axis airfields to coincide with a secondary Eighth Army offensive, he signalled: “As LRDG not trained for demolitions, suggest pct [parachutists] used for blowing ‘dromes’.” Additionally, Prendergast suggested that it would be more practical for the LRDG to transport the SAS in their trucks.

On 8 December, an LRDG patrol of 19 Rhodesian soldiers and commanded by Captain Charles ‘Gus’ Holliman left Jalo Oasis to take two SAS raiding parties (one led by Stirling, the other by his second-in-command Blair ‘Paddy’ Mayne) to the airfields at Tamet and Sirte, 350 miles to the north west. Holliman’s navigator was an Englishman, Mike Sadler, who had emigrated to Rhodesia in 1937.

The raiding party made good progress in the first two days but then hit a wide expanse of rocky broken ground, covering just 20 miles in three painstaking hours on the morning of 11 December. Soon, however, the going underfoot became the least of their problems. “Suddenly we heard the drone of a Ghibli (the Caproni Ca.309, a reconnaissance aircraft),” recalled Cecil ‘Jacko’ Jackson, one of the Rhodesian LRDG soldiers. “Not having room to manoeuvre in the rough terrain, Holliman ordered us all to fire on his command. The plane was low, and when all five Lewis guns opened up, he veered off and his bombs missed.”

The Ghibli broke off the fight but the British knew the pilot would have already been on the radio. It was only a matter of minutes before fighter aircraft appeared overhead. “We doubled back to a patch of scrub we had passed earlier,” said Jackson, who, along with his comrades, made frantic efforts to camouflage their vehicles with netting. “We had just hidden ourselves when three aircraft came over us and strafed the scrub.”

It was obvious to the Italians where the enemy were hiding, but they were firing blind all the same, tattooing the ground with machine gun fire without being able to see their targets. It was a terrifying experience for the LRDG and SAS men cowering among the patchy cover, feeling utterly helpless. All they could do was remain motionless, fighting the natural impulse to run from the fire. “I was lying face down near some scrub and heard and felt something thudding into the ground around me,” remembered Jackson. He didn’t flinch. Only when the drone of the aircraft grew so faint as to be barely audible did he and his comrades get to their feet. Jackson looked down, blanching at “bullet holes [that] had made a neat curve round the imprint of my head and shoulders in the sand.”

A member of a Long Range Desert Group (LRDG) patrol poses with a Vickers ‘K’ Gas-operated machine gun on a Chevrolet 30cwt truck, May 1942. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205196170Remarkably, the strafing caused no damage and the patrol moved off, reaching the outskirts of the targets without further incident. The plan was for Stirling and Sergeant Jimmy Brough to attack Sirte airfield while Paddy Mayne and the rest of the SAS hit Tamet. They left the following night, leaving the LRDG at the rendezvous in Wadi Tamet. At about 11.15pm, the silence was shattered by a thunderous roar three miles distant. “We saw the explosions and got quite excited, the adrenaline pumping through us,” recalled Sadler. “The SAS were similarly excited when they arrived back at the RV. We buzzed them home and on the way they talked us through the raid, discussing what could be improved next time.”

Though Stirling had drawn a blank at Sirte, Mayne had blown up 24 aircraft at Tamet. More successful co-operation between the LRDG and the SAS ensued with a five-man raiding party led by Lt Bill Fraser destroying 37 aircraft on Agedabia airfield. Mayne returned to Tamet at the end of December, laying waste to 27 planes that had recently arrived to replace the ones he’d accounted for a couple of weeks earlier.

Stirling and the SAS continued to rely on the LRDG as their ‘Libyan Taxi Service’ for the first six months of 1942, and he also looked to them for guidance in nurturing his embryonic SAS. “We passed on our knowledge to the SAS and they were very grateful to receive it,” recalled Jim Patch, who joined the LRDG in 1941. “David Stirling was a frequent visitor and he would chat and absorb things. He took advice, man to man, he didn’t just stick with the officers, he went round to the men, too.”

In the first six months of 1942, the SAS, thanks in no small measure to the LRDG, had destroyed 143 enemy aircraft. As Stirling noted:

“By the end of June, L Detachment had raided all the more important German and Italian aerodromes within 300 miles of the forward area at least once or twice. Methods of defence were beginning to improve and although the advantage still lay with L Detachment, the time had come to alter our own methods.”

For the rest of the war in North Africa, the SAS operated largely independently of the LRDG, using their own jeeps obtained in Cairo and their own navigators, now trained by the LRDG in the art of desert navigation. While the SAS conducted numerous hit-and-run raids against airfields and – following the El Alamein offensive – retreating Axis transport columns, the LRDG reverted to its original role of reconnaissance.

It was one that it accomplished with extraordinary diligence and endurance, often keeping enemy roads and positions under observation for days at a time, radioing back the vital intelligence to Cairo. With the desert war all but won, General Bernard Montgomery, commander of the Eighth Army, conveyed his thanks for the LRDG’s magnificent work in a letter to Prendergast dated 2 April 1943, praising “the excellent work done by your patrols” in reconnoitring the country into which his soldiers had advanced.

In 1984, David Stirling expressed his thanks to the LRDG in an address to an audience gathered for the opening of the refurbished SAS base in Hereford, named Stirling Lines, in honour of the regiment’s founder. “In those early days we came to owe the Long Range Desert Group a deep debt of gratitude,” said Stirling. “The LRDG were the supreme professionals of the desert and they were unstinting in their help.”

Ralph Bagnold was as unlikely a special forces commander as anyone could imagine. His war had been the Great War, when as a junior signals officer he had survived the carnage of the Western Front. When World War II began in September 1939, Bagnold was 43 and earning a comfortable living as a scientist and writer.

Recalled to the colours four years after he had retired from the army, Major Bagnold was posted to Officer Commanding, East Africa Signals, and dispatched on a troopship to Kenya. But he never arrived. In early October, Bagnold’s vessel, RMS Franconia, collided with a merchant cruiser in the Mediterranean. He and the rest of his troop transferred to another vessel and sailed to Port Said in Egypt to await the first available ship to Kenya.

Bagnold was delighted. Egypt was a country he knew well, better in fact than nearly any other Briton. He had spent most of the 1920s in Egypt with his regiment, entranced by the culture and the vast desert that stretched west into Libya. In 1927, he made his first foray into the Libyan desert, leading a small band of explorers in a fleet of Model T Fords. More expeditions followed, penetrating farther into the desert’s brutal interior than any other European had. Bagnold’s fascination was as much motivated by science as by exploration, and he began studying the terrain, leading him to publish the critically acclaimed The Physics of Blown Sand And Desert Dunes in 1939.

Back in Egypt, Bagnold took the train from Port Said to Cairo to look up old friends. He dined with one such acquaintance in the restaurant of the exclusive Shepheard’s Hotel, where he was spotted by the gossip columnist of The Egyptian Gazettenewspaper. A few days later, the word was out that Bagnold was back in town, and within a matter of days he was summoned to the office of General Archibald Wavell, General Officer Commanding-in-Chief of Middle East Command.

Wavell pumped Bagnold for information on the accessibility of the Libyan Desert – the general was increasingly concerned by intelligence reports that the Italians had as many as 250,000 men in 15 divisions under Marshal Rodolfo Graziani. So impressed was he by what Bagnold told him that Wavell arranged for his permanent transfer to North Africa.

General Sir Archibald Wavell, Commander-in-Chief Middle East, at his desk, 15 August 1940. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205193528Bagnold’s vision brought to lifeBagnold was sent to Mersa Matruh – 135 miles west of Cairo – where he discovered that the most up-to-date map the British forces possessed of Libya dated from 1915. He was similarly appalled by the indifference of senior officers to the threat posed by the Italians – they believed the enemy would make a full-frontal attack on Mersa Matruh, which they would easily repel, but Bagnold suspected the Italians, some of whom he had encountered during his expeditions of the 1920s, would launch surprise attacks on British positions in Egypt from further south.

Bagnold’s idea was to form a small reconnaissance force to patrol the 700-mile frontier with Libya. This was rejected, as it was when he submitted it again in January 1940, and the following month Bagnold was posted as a military advisor to Turkey, presumably to give Middle East Headquarters (MEHQ) in Cairo some peace and quiet.

But Bagnold wouldn’t give up, and after Italy declared war on Britain on 10 June 1940, he tried for a third time to convince the top brass of his idea, explaining in an additional paragraph that there would be three patrols:

“Every vehicle of which, with a crew of three and a machine gun, was to carry its own supplies of food and water for three weeks, and its own petrol for 2,500 miles of travel across average soft desert surface… [each] patrol to carry a wireless set, navigating and other equipment, medical stores, spare parts and further tools.”

This time Bagnold entrusted his friend, Brigadier Dick Baker, to ensure the proposal was put directly into the hands of Wavell. Baker obliged and within four days of receiving Bagnold’s proposition, Wavell had authorised him to form the new unit, provisionally entitled the Long Range Patrol (LRP).

Wavell was a hard taskmaster, however, giving Bagnold just six weeks to make his vision a reality. Men, equipment, rations, weapons, vehicles… it was a formidable challenge but one that Bagnold rose to. First, he searched for the soldiers; he tracked down most of his old companions from his exploration days, and while one or two were unable to secure a release from their military duty, Bagnold was soon joined in Cairo by Bill Kennedy-Shaw and Pat Clayton, who by 1940 had accumulated nearly 20 years of experience with the Egyptian Survey Department. Also recruited to the new unit was captain Teddy Mitford, a relative of the infamous sisters and a desert explorer in his own right during the late 1930s.

While Clayton, Mitford and Kennedy-Shaw started to hunt down the necessary equipment, Bagnold flew to Palestine on 29 June to see Lt-General Thomas Blamey, commander of the Australian Corps. Bagnold requested permission to recruit 80 Australian soldiers, explaining that in his view Australians would be the Allied soldiers most likely to adapt quickest to desert reconnaissance. Blamey, on the orders of his government, refused, so Bagnold turned to the New Zealand forces in Egypt.

This time he met with success, and 80 officers, non-commissioned officers and men from the New Zealand Divisional Cavalry Regiment and Machine-Gun Battalion volunteered to be part of the LRP. Bagnold took an instant shine to the Kiwis, saying:

“They made an impressive party by English standards. Tougher and more weather-beaten in looks, a sturdy basis of sheep-farmers, leavened by technicians, property-owners and professional men, and including a few Maoris. Shrewd, dry-humoured, curious of every new thing, and quietly thrilled when I told them what we were to do.”

July was spent assembling the vehicles and equipment and training the New Zealanders in the rudiments of desert motoring and navigation. Kennedy-Shaw, appointed the unit’s intelligence officer, told the Kiwis that the Libyan Desert measured 1,200 miles by 1,000 – or put another way, was roughly the size of India. It was bordered by the Nile in the east and the Mediterranean in the north. In the south, which was limestone compared to the sandstone in the north, the desert extended as far as the Tibesti Mountains, while the political frontier with Tunisia and Algeria marked its western limits.

A well-loaded Chevrolet truck about to set off on patrol from Siwa. This vehicle was crewed by New Zealanders, many of whom joined the Long Range Desert Group in 1940 from a consignment of troops who found themselves at Alexandria without their arms and equipment, which had been lost at sea. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205125571The unit proves its worthBy the first week of August 1940, the unit was ready for its first patrol and the honour fell to 44-year-old Captain Pat Clayton. He and his small hand-picked party of seven left Cairo in two Chevrolet trucks. Crossing the border into Libya, they continued on to Siwa Oasis, where Alexander the Great had led his army in 332 BCE. “The little patrol of two cars then struck due west, exploring, and made the unwelcome discovery of a large strip of sand sea between the frontier and the Jalo-Kufra road,” wrote Clayton in his subsequent report. “The Chevrolet clutches began to smell a bit by the time we got across, but the evening saw us near the Kufra track.”

They laid up here for three days, taking great care to conceal their presence from the Italians, as they observed the track for signs of activity. They returned to Cairo on 19 August, having covered 1,600 miles of the barren desert in 13 days.

Clayton and Bagnold reported their findings to General Wavell, who, having heard an account of the unit’s first patrol, “made up his mind then and there to give us his strongest backing.” A week later, Wavell inspected the LRP and told them he had informed the War Office they “were ready to take the field.”

Bagnold split the LRP into three patrols, assigning to each a letter of no particular significance. Captain Teddy Mitford commanded W Patrol, Captains Pat Clayton and Bruce Ballantyne (a New Zealander) were the officers in charge of T Patrol and Captain Don Steele, a New Zealand farmer from Takapu, led R Patrol. Each patrol consisted of 25 other ranks, transported in ten 30-cwt Chevrolet trucks and a light 15-cwt pilot car. They carried rations and equipment to sustain them over 1,500 miles and for armament each patrol possessed a 3.7mm Bofors gun, four Boys AT (anti-tank) rifles and 15 Lewis guns.

For the next two months the LRP reconnoitred large swathes of central Libya, often enduring daytime temperatures in excess of 49 degrees Celsius as they probed for signs of Italian troop movements.

On 19 September, Mitford’s patrol encountered two Italian six-ton lorries and opened fire, giving the aristocratic Englishman the honour of blooding the LRP in battle. In truth, it wasn’t much of a battle; the Italians, stunned to meet the enemy so far west, quickly waved a white flag. The prisoners were brought back to Cairo, along with 2,500 gallons of petrol and a bag of official mail.

General Wavell was delighted, not just with the official mail that contained much important intelligence but with the LRP’s work throughout the autumn of 1940. Bagnold capitalised on the praise with a request to expand the unit, suggesting to Wavell that with more men he could strike fear into the Italians by launching a series of hit-and-run attacks across a wide region of Libya. On 22 November, Bagnold was promoted to acting lieutenant-colonel and given permission to form two new patrols and reconstitute the Long Range Patrol as the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG).

For his new recruits, Bagnold turned to the British army and what he considered the cream: the Guards and the Yeomanry Divisions. By the end of December, he had formed G (Guards) Patrol, consisting of 36 soldiers from the 3rd Battalion The Coldstream Guards and the 2nd Battalion The Scots Guards, commanded by Captain Michael Crichton-Stuart. Y Patrol was raised a couple of months later, composed of men from, among others, the Yorkshire Hussars, the North Somerset Yeomanry and the Staffordshire Yeomanry. For their inaugural operation, however, G Patrol was placed under the command of Pat Clayton, whose T Patrol would offer support.

Two Long Range Desert Group patrols meet in the desert. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205194946A successful first missionTheir target was Murzuk, a well-defended Italian fort in south-western Libya, nestled among palm trees with an airfield close by. The fort was approximately 1,000 miles to the west of Cairo as the crow flies, and reaching it entailed a gruelling journey that lasted for a fortnight. There were 76 raiders in all, travelling in 23 vehicles, including nine members of the Free French who had been seconded to the operation in return for flying up additional supplies from their base in Chad.